Author and Lean expert Tim Wolput works and lives in Japan. He is connected to the Toyota Management Institute and started cooperating with the Obeya Association through his valuable contributions to the Worldwide Obeya Summit 2022

This revolutionary new Obeya footage contains research on historic Obeya timelines that have never been shown before.

By bridging Obeya back to its origins we learn about the deep philosophical essence from decades of Obeya use and centuries of practice in the Art of Management.

Organizations use an Obeya as an effective instrument to execute strategy and involve people. Creating a place where people come together to develop a clear understanding about the who, why, what, how and when.

The use of the word Obeya as a management practice is relatively new, but the ideas behind Obeya practice have been around for a long time. Good examples can be seen in Japanese companies like Toyota, where people have been working along these principles since their early days.

The Art of Management of which Obeya originates goes back to the ancient wisdom of Confucius. The Art of Management is not a linear process, but rather something that moves in an upward spiral-like direction, building experience upon experience.

“The Japanese word ‘Do (道)’ is essential as it points towards a path of improvement”

The Analects of Confucius and the Art of Management

“CHIKO-GOITSU” (知行合一) as the Japanese say, is based on the teachings of Confucius more than 2000 years ago. It means: ’Knowledge and Action are One’. Knowledge without taking action is empty knowledge: unused inventory of information. True wisdom, according to Confucius, is gained by taking action followed by reflection and putting the learned lessons back to the test. In doing so, one creates an upward spiral of learning. This is a Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle avant la lettre. Confucius advised to make this a daily practice.

Confusius- Roots of Lean

Samurai Warrior – Photograph by Felice Beato, c1866.

In Japan The Analects of Confucius (551 BC – 479 BC) are considered an extremely important resource for learning the Art of Management.

Confusius was considered to be a role model for all teachers. Arguably every manager in Japan at one time or another seeks for guidance in The Analects.

The old warriors of the 12th century Japan, the Samurai, also knew Chiko-Goitsu – and put it into practice. The ‘bible’ of the Samurai, a book called the Hagakure, describes how a Samurai used to write down his mistakes on a daily basis in order to learn from them and develop himself into a better Samurai. The Samurai lived by a code: The Way Of The Warrior (BUSHIDO 武士道). The Japanese word ‘Do (道)’ is essential as it points towards a path of improvement. We can find the word ‘Do’ in many Japanese traditions: Kendo (the Way of the Sword), Judo (the Way of Gentleness) and Sado (the Way of Tea).

All these traditional practices share a strong focus on ‘Doing in order to Develop’. Learning takes place in the DOJO or the ‘Place where the way is practiced’. The concept of a room where people gather and develop themselves is starting to take shape throughout history.

Current use of Obeya in Japan

For most Japanese people 大部屋 (Obeya) just means how it literally translates: a ‘big room’. Nothing more to it, or is there?

Don’t Japanese people know about Obeya as it is known in the Western world? Have we in the West been doing something that we thought was Eastern philosophy, but is in fact a bunch of mumbo jumbo or false interpretation?

On the work floor at factories in Japan often there are spaces next to the production line called ‘Kunren Dojo’ or the ‘Training Dojo’. It is a space where employees can practice and master the skills necessary to perform the work. These spaces are specifically not in a separate building or classroom. Training is done where it is most relevant, namely at the workfloor or ‘GEMBA’.

At the Nissan ‘Mother Plant’ in Yokohama, where Nissan trains overseas employees, they took this concept even a step further and shaped the training dojo into an Obeya right at the production floor.

Much like the Samurai would reflect upon their daily actions, we can return to the idea of CHIKO-GOITSU in modern days. Organizations that are implementing Toyota style Management in Japan, have a practice that is also known in the Agile and Scrum world: KEEP-PROBLEM-TRY (KPT).

A difference between Japan and the Western worlds is that in Japan KPT is more aimed at changing habits and creating a team or company culture – than at improving performance only.

Every Obeya must be seen as a manifestation of the principle of GENCHI-GENBUTSU – it is the closest thing to the “actual place and things”.

Each Toyota style Management Obeya has a spot on the wall reserved for this daily reflection practice. It is an essential part of the Way of Management. In this sense the Obeya like the DOJO has become a place where management is put into practice and people reflect upon the actions they took, thus helping each other to develop oneself.

Exactly in line with Confucius’ upward learning spiral of CHIKO-GOITSU.

GENCHI-GENBUTSU ‘The actual place and the actual things’

The Way of Management teaches us to understand what is happening right there and then at the GEMBA. This is known as GENCHI-GENBUTSU (現地現物)or ‘the actual place and the actual things’. This might sound obvious in a manufacturing environment. But how to apply this in for example the service industry? On a factory floor work and processes are visible right in front of you, but in an office environment usually the only things you can see are a bunch of computers. Thus, the question is: what would GENCHI-GENBUTSU look like in a non-manufacturing environment?

Every Obeya must be seen as a manifestation of the principle of GENCHI-GENBUTSU – it is the closest thing to the “actual place and things”. When there are no physical production lines or factory floors in the organization, this principle still applies. The Obeya is the closest as you can get to the actual value creation process.

“For Japanese people the Obeya is an extension of the idea of the work floor or GEMBA. Hence, it is hard for Japanese people to understand that managers would exist without stepping one foot in the GEMBA.”

Japan has always had a GEMBA-oriented approach rooted in the practicality of the craftsman. Like Toyota says: ’Good Thinking, Good Products’ – and ideally the thinking also takes place at the place where the good products are being made. Because in order to improve you need to be able to clearly grasp what is happening in order to make the right decisions. Again we observe a non-linear process, Continuous Improvement moving in an upward spiral-like direction. Japanese companies understand that continuous improvement is driven by people. When you create an environment that allows and stimulates good thinking, good products will follow. That is why Toyota says that they ‘Develop People First’ (monozukuri = hitozukuri) or why Panasonic believes that ‘People Come First’ (ningendaiji).

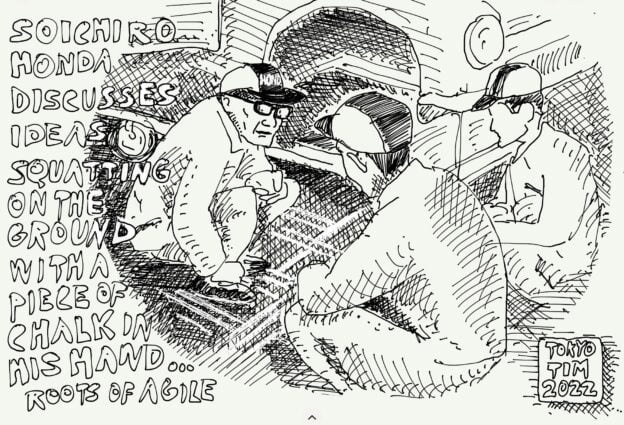

Together with Toyota, Honda is considered to be influencing the Agile movement. There is a famous picture of So’ichiro Honda, squatting on the factory floor making chalk drawings on the concrete floor discussing product improvements with his team. They were working along the principles of Agile before the days of software development. Strange enough, at one point Honda decided to move their design and development department to a geographically separated location far away from the production site. Honda suffered the consequences. Resulting in poor product development process and poor business results. When with the realization of their N-box car, they put their design department physically back in the same building as the production department, the results were returning accordingly. The N-box became a huge success. This shows how powerful working together at the Gemba really is. If you lose sight of Genchi-Genbutsu, chances are you might not succeed.

So’ichiro Honda, discussing product improvements with his team

Toyota Way management defines ‘work’ as ‘creating value’. In boardrooms no value is being created, so work done here does not count as real work according to this principle. That’s why one of Toyota’s goals is to have ‘Zero-meetings’. They do this by getting all the relevant people together at the place where value is created, the GEMBA, and by making sure the value creation is visible (visual management). This way, it is possible to have meaningful communication, decision-making and real-time implementation based on up-to-date facts. There is no time or information loss by having to write and read reports or having to arrange board room meetings. In other words, the speed of management increases dramatically. Another great effect is that you can get rid of the traditional idea of control management, where before the manager used to give instructions and people only did as they are told.

Obeya style working allows people to understand the current situation in real-time, so they can see what needs to be done without a manager needing to give them specific instructions. This creates an energy boost in people as they can decide on their own actions, which in turn lead to a sense of fulfillment. In Japan this is called ‘re-energizing the work floor’ and it is one of the main reasons why Obeya is such an effective practice. In this context an often-heard expression is ‘no energy, no results’. One could even argue that the primary focus of an Obeya is not achieving the results but rather to create the conditions of a re-energized work floor in order for results to be achieved.

For Japanese people the Obeya is an extension of the idea of the work floor or GEMBA. Hence, it is hard for Japanese people to understand that managers would exist without stepping one foot in the GEMBA.

A great example of an Obeya put to use in order to create energy and understanding is the Obeya of an accounting office in Tokyo, called Oishi Accounting. They are a Great Place to Work and have actually turned their office into one big Obeya that is entirely focused on creating a positive company culture. Check the video below to see how they are doing this.

Obeya: connecting the East to the West

Obeya at Oishi accounting – Tokyo

Obeya: connecting the East to the West

A ‘big room’ is a place where people come together and get work done, a place where a lot of things happen, lives get entwined, stories are told, history is made. This is what makes the actual room so important: it’s a place where people find each other, interact and unique moments happen.

There’s a little Zen story I was told by a Buddhist priest that perfectly illustrates all of the above, and at the same time sheds light on why an Obeya doesn’t always work well when its essence is forgotten:

‘Once there were two kids, a boy and his younger brother. Both were thirsty but they only had one bottle of water. So, they somehow needed to divide the content among the two of them.’

Here, the priest asked what the best way would be to share the water. Most rational people would say that the most preferable way would be to find a way to divide the water in equal parts. And right they are. Both brothers have an equal amount of water, so nobody loses, end of story.

However, the priest mentioned that in Zen there is a more virtuous way of dealing with this situation:

The older brother would give the bottle to his younger brother and say: ‘drink as much as you like but leave a little bit for me to drink.’ The younger brother would drink and after a few sips he would hand the bottle back to his brother so that he then could drink, as he knows that his brother is also thirsty. In this way the bottle goes back and forth until it is finally empty.

Here, both brothers have quenched their thirst, but at the same time much more took place… By sharing the water, an ongoing interaction between the two brothers was initiated. The sharing of the water created multiple contact points that reinforced their relationship and trust in each other.

Equally dividing the content is a typical result-oriented approach. You may get the result but nothing more than that.

The latter approach of sharing the water on the other hand, shows a true understanding of what is important for us human beings: connection, interaction and sharing energy with each other.

Herein lies the secret magic that makes Obeya so much more than just a room with goals, targets, graphs and data on the wall. It is a place of learning and connection, steeped in centuries of tradition.